The Science of Tea

Tea is filled to the brim with a rich history spanning several millenia. We have historical documents which show that tea was produced and appreciated as early as 1,100 BC in southwest China[1]. And according to legends, it’s believed that in 2737 BC, the servants of the mythic emperor Shennong were boiling water to remove its impurities for him to drink. A dead leaf from a tea bush fell in, and was presented to the emperor with its brownish color gone unnoticed. The emperor took a liking to the taste, and thus tea was born.

Photo-lithograph of the Huayang Guozhi—Bazhi, the oldest document to mention tea

Photo-lithograph of the Huayang Guozhi—Bazhi, the oldest document to mention tea

One might think it’s simply a matter of plucking leaves and steeping them in hot water, akin to the legend, but every aspect of its production and preparation is nailed down to a science to chemically and biologically alter the leaves to produce the tastiest and least-bitter cup possible. In 760 CE, Lu Yu, an orphan adopted by a Buddhist monk (and promptly ran away to join the circus), dedicated years of his life to chronicle all of his knowledge on tea believing it to be an expression of the harmony and unity of the universe.

A Thousand mountains will greet my departing friend,

When the spring teas blossom again.

With such breadth and wisdom,

Serenely picking tea—

Through morning mists

Or crimson evening clouds—

His solitary journey is my envy.

We rendezvous at a remote mountain temple,

Where we enjoy tea by a clear pebble fountain.

In that silent night,

Lit only by candlelight,

I struck a marble bell—

Its chime carrying me

A hidden man

Deep into thoughts of ages past.

— “The Day I Saw Lu Yu off to Pick Tea” by Huangfu Zeng (~700 CE)

Types of Tea

The most crucial aspect of harvesting tea, and what differentiates a green tea from a red tea (which is what the West calls black tea[2], but will be refered to here as red tea from henceforth), is how long the leaves are oxidized. When the tea leaves are plucked and exposed to oxygen, their cell walls break down and gradually blacken in color. Through this process, the bitter polyphenols, catechins, are converted into less bitter polyphenols, tannins, which are richer and astringent, often giving a malty or fruity taste.[3]

Once the leaves reach the desired level of oxidization, they are heated up to stop the oxidization process, usually by steaming or roasting which has its own impact on how the tea will taste. Japanese green teas are generally steamed, which helps retain its green hue and vegetal taste, while Chinese green teas are roasted imparting a toasty flavor and a more yellow hue. Red teas are gently dried in the sun to reach the highest levels of oxidization without it going stale. A fun outlier is lapsang souchong, a chinese red tea roasted over a fire of pine, resulting in a very smoky aroma and taste.

There are quite a lot of steps before tea makes it to your cup.

There are quite a lot of steps before tea makes it to your cup.

Red teas are the most oxidized (80% - 95% oxidized). They are rolled upon plucking to damage them, speeding up the oxidization process. They can have the widest range of flavor, as less bitter catechins remain to mask the flavors picked up from their environment.

Green teas are the least oxidized (1% - 3% oxidized), and are heated up immediately after they’re plucked. They taste vegetal and grassy, and are steeped at a lower water temperature to extract less of the bitter catechins.

Oolong teas have the broadest range of oxidization (10% to 80% oxidized). Consequently, their flavor widely varies. A less oxidized oolong will taste more vegetal and floral like a green tea, while one on the higher end of oxidization might be rich and malty like a red tea.

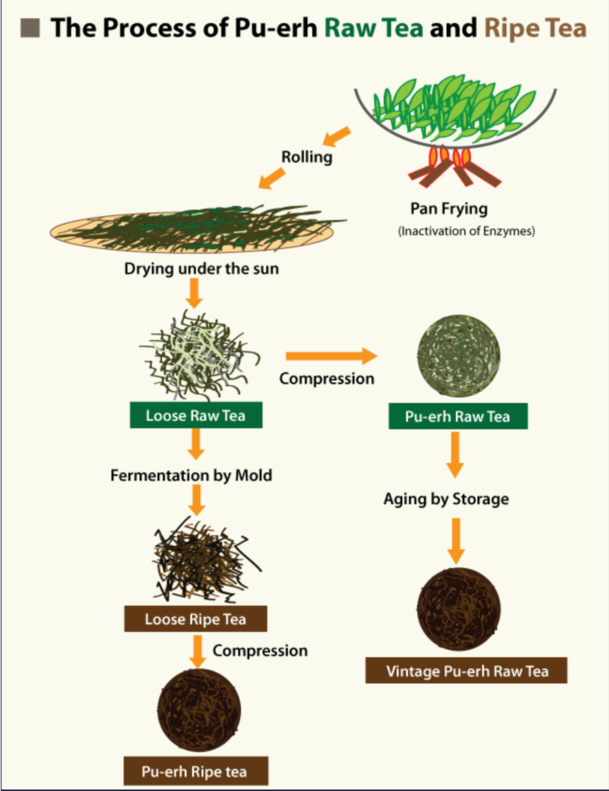

Black tea (again, not what the West calls black tea) brings an entirely new element to the mix. It’s not determined by its level of oxidization, but whether the leaves are fermented. Microbes break down compounds in the leaves, altering their flavor profile. There are two different methods to age the tea. Raw black tea refers to the traditional method where you simply stow the tea away to slowly ferment over the years, peaking at roughly 50 years before the leaves begin to degrade. Ripe black tea refers to a new technique discovered in 1973, where the leaves are stored in large piles in a humid environment and splashed with water, turning them every other day for up to a month. They’re then stowed away like a raw black tea, but peak in quality in only 20 years. These fermented teas tend to have a musty smell and taste earthier as the years go by. They are the aged wines of tea, and can be just as expensive.

Pu-erh is fermented tea from Yunnan, China

Pu-erh is fermented tea from Yunnan, China

CTC tea, or bagged tea, is what you’ll find at your grocery store. They are crushed, teared, and curled by machinery into small pellets. It was invented in 1930 to meet the increasing demand for tea in a global economy. They tend to use low quality leaves, which are then stressed and heavily damaged by the CTC process, and take months before they land on a store’s shelf, resulting in unavoidable bitterness that mask the more desirable flavors.

Other Factors

Which season the tea is harvested plays a significant role in their quality. With a spring harvest, the leaves have weathered through winter and pick up a lot more flavors from their environment. With a late-spring/summer harvest, the tea plants grow rapidly, but have less time to capture as much flavor. For autumn harvests, the plants are dying as winter approaches and are the least desirable.

Sunlight exposure has its own chemical reaction that influences the taste of the tea. Exposure during growth lowers the amount of full/creamy-tasting amino acids. Gyokuro, the highest grade of Japanese green tea, must be harvested in the spring and partially shaded during growth.

There will also be differences in tea by their location, due to the climate they’re grown in and which varietal of tea plant species they are. For example, teas grown in India generally produce a stronger red tea than those grown in the various provinces of China. There’s even a relatively new varietal grown in Kenya called Purple Tea, named for their vibrant purple leaves.

And of course, the tea to water ratio, steeping time, and water temperature[4] are integral to getting the perfect cup of tea. Red teas are tougher due to their high oxidization and thus can be steeped at a boiling temperature for 3-5 minutes, extracting the most out of the leaves. Oolong can generally handle 190 - 200f, with green tea the most sensitive at 170 - 180f. If they’re steeped for too long, more of the bitter catechins will be extracted and take over. This is also why it’s important to be sure to filter out any small particulates of the leaves to prevent oversteeping. High quality leaves will have less “dust” you need to filter out due to their freshness and tenderness; the leaves turn more brittle as time passes.

Gongfu Cha

To get the most out of your finest red or black tea, you can also try your hand at gongfu cha. It essentially means skillful brewing of tea, and is an artform in itself. Instead of the traditional Western method of brewing a teaspoon of tea in a cup’s worth of water for a few minutes, you brew ~1.5 teaspoons of tea in half a cup of water and let it steep for only a few seconds[5]. This first steep opens up the leaves to bring out more flavor, but the liquor will be weak and unimpressive. It’s only used to warm up your teaware before finally pouring it out. You then heat up the water again and steep the leaves for ~10 seconds, adding 10 to 15 seconds with each subsequential steep. You will be able to taste the different flavor profiles of the tea with every steep until you tire out the leaves and the strength of the flavors weaken.

A slotted tray for gongfu cha, to capture the first discarded pour and any accidental spills.

A slotted tray for gongfu cha, to capture the first discarded pour and any accidental spills.

There’s a lot more to be said on the production and preparation of tea, but hopefully this whets your appetite to dive into the world of loose leaf teas! If you’re interested in giving it a try, I use this single-serve cup infuser on a daily basis.

Footnotes

[1] Found in the Huayang Guozhi—Bazhi - A local gazetter from ~350AD in southwest China consisting of biographies of various rulers, including King Wu of the Zhou Dynasty and his 1066 BC expedition against eight principalities, whereby tea was used as tribute offerings.

[2] The East classified their teas by the color of the liquid after it’s brewed. It’s thought that a simple mistranslation between western and eastern traders resulted in the West believing the distinction was based on the color of the leaves. To add to the confusion, red teas in the West are now associated with rooibos tea. And finally, there’s debate on how oolong got its name (literally “black dragon”), but it’s likely referring to the color and shape of the leaves, breaking the usual system of classification.

[3] Heavier polyphenols, known as tannins, taste less bitter than lighter ones like catechins. The reason for this is still a mystery to this day!

[4] It’s also very important to use clean purified/spring water. You will notice a night and day difference in taste using filtered water versus unfiltered tap water. The hardness of tap water will simply make it taste funky.

[5] The ratio of tea to water actually varies by the shape of the tea leaves and whether it’s compressed (which is common for fermented teas as they are stored this way), but these measurements should get you in the right ballpark. Ideally you should use a scale to measure the tea’s weight, as teaspoons are unreliable to determine how much tea is in your cup.